Everyday we hear about civil wars and conflicts in different parts of the world that can seem far removed from our everyday lives. But there was a time when Kansas was at the center of a bitter and oftentimes brutal struggle between abolitionists and pro-slavery supporters. It wasn’t called Bleeding Kansas for nothing.

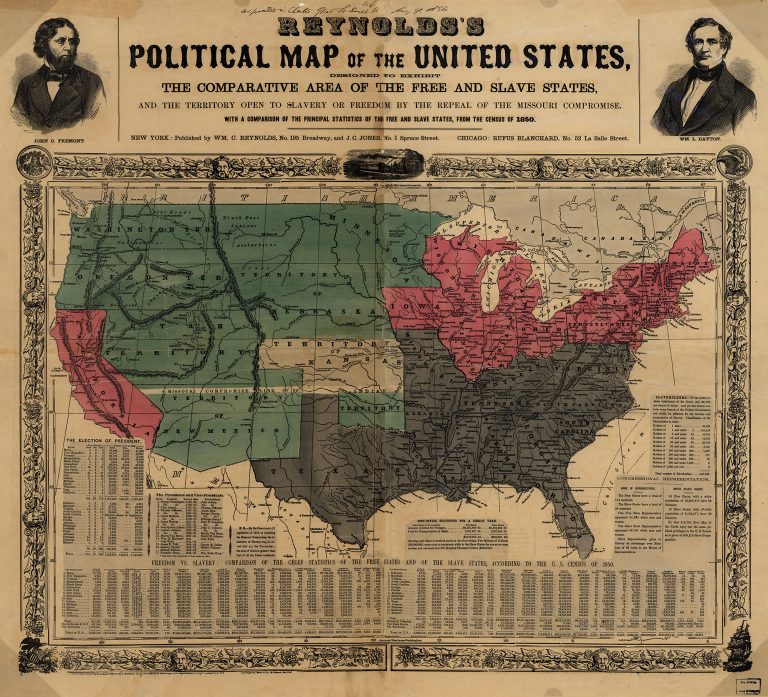

The trouble started in 1854, with passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, opening Kansas Territory to settlers who would then vote whether to be admitted into the Union as a slave or free state. While it seemed like an equitable solution to US Senator Stephen A. Douglas, who sponsored the bill and for whom Douglas County is named, in reality it turned out to be a terrible idea, unleashing a chain of events that led to increasingly violent confrontations between pro-slavers and abolitionists. In fact, it was out-and-out guerilla warfare, with skirmishes, battles, daring rescues, theft, gunpoint robbery, cold-blooded murder and massacres. There were plenty of shady and colorful characters, too, including abolitionist John Brown, who once rode into Lawrence virtually bristling with rifles, bayonets, swords and other warfare, and Sheriff Samuel Jones, who must have hated Lawrence with a passion. Things got so ugly, some say it was the true start of the Civil War, which officially didn’t begin until 1861.

Although Kansas Jayhawkers and Missouri Bushwhackers both committed atrocities up and down the Kansas-Missouri border, it was in our neck of the woods that the era’s most historic and horrific events took place. That’s not surprising, considering that abolitionists founded Lawrence just months after the Kansas-Nebraska Act for the express purpose of preventing the territory from becoming a slave state. That prompted slavery supporters from Missouri to pour into Kansas Territory, especially for the March 1855 election for a territorial legislature, with an estimated 800 to 1,000 Missourians arriving in Lawrence to vote illegally. According to Sara Robinson, who wrote eloquently about her life in early Lawrence, the Missourians were “armed with guns, pistols, rifles and bowie knives.” Another election was called, with more to follow.

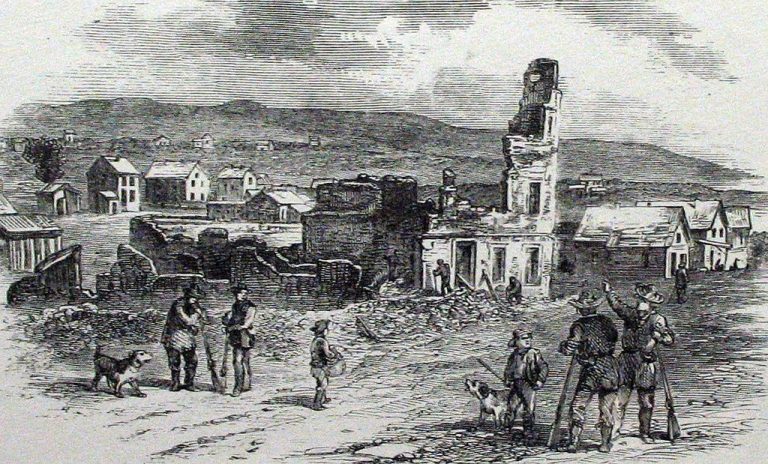

In November 1855, a pro-slavery man shot and killed an abolitionist, yet it was free-state supporter Jacob Branson that Sheriff Jones arrested for purportedly making threats. After Branson was rescued from jail and taken to Lawrence, the sheriff considered it a fine excuse to bring about 1,500 to 2,000 proslavery Missourians to an encampment about three miles south of Lawrence on the Wakarusa River. The weeklong siege, known as the Wakarusa War, ended in a truce. Lawrence wasn’t so fortunate the following year, when on May 21 Missourians under the command of Sheriff Jones sacked Lawrence, destroying abolitionist newspaper presses and burning the Free State Hotel, businesses and houses to the ground, including the home of Sara Robinson. And then things got really bad.

On May 24, John Brown and four of his sons retaliated the sacking of Lawrence with a massacre at Pottawatomie, hacking five pro-slavery settlers to death with swords and thereby shocking the nation. The summer months of 1856 brought more confrontations, including the Battle of Black Jack in which John Brown captured about 30 pro-slavery militiamen who had been sent to capture him, followed by Brown’s attack on the pro-slavery settlement of Franklin to recover rifles and ammunition looted in the sack of Lawrence. Free-staters attacked and defeated pro-slavers at Fort Titus near Lecompton, and then, after Brown rustled about 150 head of cattle near the Missouri border and brought them to Osawatomie (Brown reportedly declared he was only converting the herd to abolitionism), the Battle of Osawatomie left eight dead, including Brown’s youngest son.

Meanwhile, as Jayhawkers and Bushwhackers kept diligently killing each other, between 1855 and 1859 both sides of the slavery issue drafted four different constitutions, with the last one finally approved by a wide margin of Kansas voters. With Kansas admitted to the Union as a free state in 1861, the period known as Bleeding Kansas came to an end, though Kansas hardly stopped bleeding. The worst occurred on August 21, 1863, when William Clarke Quantrill and some 400 pro-slavery ruffians rode into Lawrence and killed more than 180 men and teenage boys and laid the town to waste.

To try to get a handle on all the various events quickly unfolding in and around Lawrence during it’s early years–which to me are as confusing and chaotic as real life must have been back then–I suggest the Watkins Museum of History, where there’s a storyboard timeline of major events and conflicts. On display are also artifacts, including a fragment of a printing press, thought to have been damaged during the sack of Lawrence and salvaged from the Kansas River, and a rocking chair belonging to Sara Robinson, whose husband became the first governor of Kansas.

To get a more hands-on feel of Bleeding Kansas, Black Jack Battlefield, near Baldwin and the scene of an intense three-hour skirmish, offers hiking trails and a self-guided tour to areas where fighting occurred. Another good destination is Lecompton, where you can tour Constitution Hall, privately built by Sheriff Jones in 1856 to house the pro-slavery territorial legislature and with displays relating to the territory’s first, pro-slavery constitution and how events there split the Democratic party and thereby ushered in Abraham Lincoln’s presidential win. Nearby is the handsome Territorial Capital Museum, built in 1855 as the Kansas State Capitol (the honors, of course, went to Topeka) and now serving as a museum housing an eclectic collection of historic items, including artifacts from the Battle of Fort Titus.

As I was researching and writing this article, I found it instructive to reflect that while we might lament the political divide that exists in our country today, it’s nothing compared to what it was like back then.

Explore deeper into Douglas County's Bleeding Kansas Story at Civil War on the Western Frontier, August 17-19. Historical agencies throughout Douglas County will present programs that explore Quantrill’s Raid and highlight our area’s territorial and Civil War history. Learn more>

Beth Reiber

Beth Reiber

A Lawrence native, Beth Reiber has been a travel writer for more years than she cares to remember. After living in Germany and Japan, she returned to her hometown, raised two sons and now enjoys cooking, gardening, hanging out with family and friends and exploring Lawrence as much as she loves traveling the world.