Historic Sites of Quantrill’s Raid

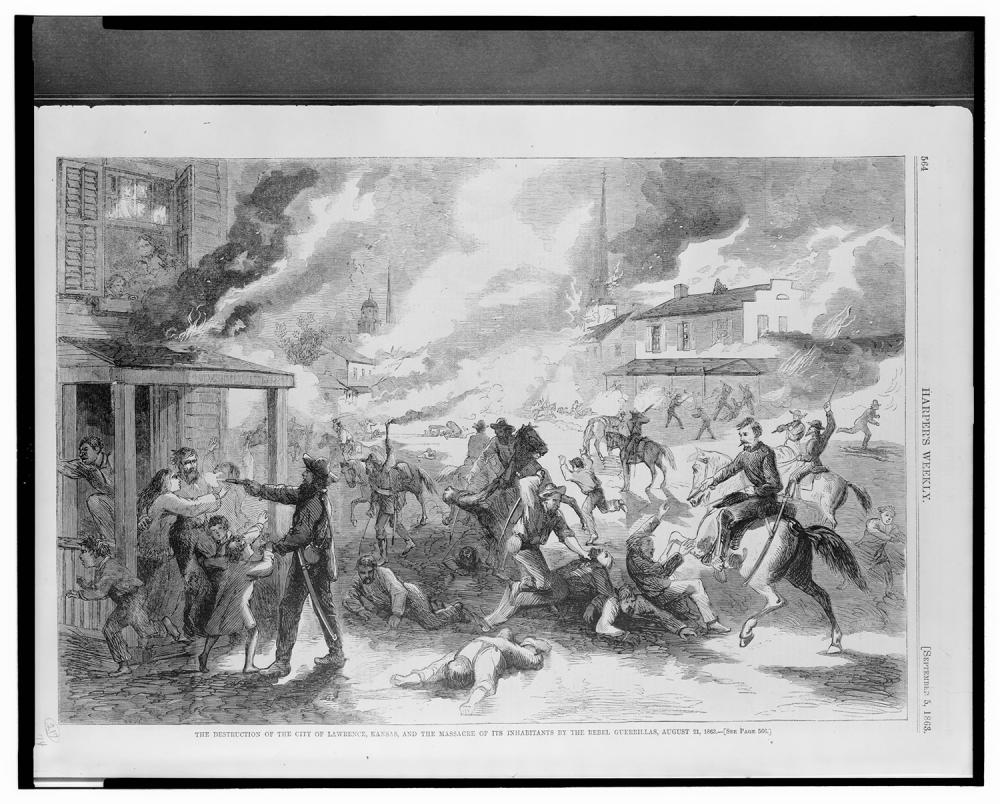

Engraving of Quantrill’s Raid from Harper’s Weekly, September 5, 1863 (Library of Congress)

Many people would agree that after more than 150 years, William Quantrill’s raid on Lawrence—also known as the Lawrence Massacre—remains our city’s defining event. On August 21, 1863, Quantrill’s Confederate guerillas attacked the town, killed about 200 men and boys, and destroyed as much as two million dollars worth of property. Following this devastating attack, Lawrence quite literally rose from the ashes as survivors quickly rebuilt their town and made it more prosperous than before. Ever since, the raid and its aftermath have symbolized the resilience of Lawrence and its people.

Despite the raid’s destruction and the citywide development that has marked Lawrence in the years since evidence of that harrowing day remains to be seen by historically conscious travelers.

1111 E 19th Street

THE FIRST LAWRENCE VICTIM

MILLER HOUSE

Riding west along the Oregon Trail, Quantrill’s men reached the outskirts of Lawrence just before dawn on August 21. Not far from the Miller House—which served as an Underground Railroad station and survives today—they killed the Rev. Samuel S. Snyder, a minister of the United Brethren Church and chaplain to black Union troops.

“Mr. Snyder was up and in his cow yard – which is located along the road – milking. They halted as soon as they came within close pistol range and commenced firing at him. Their aim was deadly; he fell at the first discharge…and expired in a few minutes. He was the first victim of the unparalleled slaughter which followed.”

Hovey E. Lowman

Raid Survivor

NW Corner of 11th & Mass Street

RUSH ON TO THE TOWN

WATKINS MUSEUM OF HISTORY

As dawn broke on August 21, 1863, Quantrill’s 400 men entered what was then the outskirts of Lawrence, riding through South Park toward the Eldridge House at the foot of Massachusetts Street. At the corner of what is now 11th and Massachusetts, a squad went to the top of Mount Oread to watch for federal troops. The main body—shouting “On to the hotel!” and other battle cries—continued their ride down Massachusetts Street as smaller bands tracked along Vermont and New Hampshire.

We recommend you visit the nearby Watkins Museum of History—where admission is free—to view artifacts and images from the raid and other stories from local heritage.

“When they came to the high ground facing Massachusetts Street, not far from where the park now is, the command was given in clear tones, ‘Rush on to the town.’ Instantly the whole body bounded forward with the yell of demons.”

Rev. Richard Cordley

Rev. Richard Cordley

Lawrence resident

1200 Oread Avenue

KEEPING WATCH FOR YANKEES

OREAD HOTEL

From the bare top of Mount Oread, the guerillas’ observation squad scanned the countryside (then largely treeless prairie) for any sign of approaching Union forces. Today, you can enjoy an even better vantage point: the ninth-floor balcony of the Oread Hotel.

“Eleven rushed up to Mount Oread to keep watch of the country round about. From here they could see over the whole country for several miles, and note any gathering among the people to come to the rescue.”

Rev. Richard Cordley

Rev. Richard Cordley

Lawrence resident

Corner of 10th & Massachusetts Street

FORTUNATE MEN

CORNER OF 10TH & MASSACHUSETTS STREET

The raiders rode downtown, yelling and shooting at every man they saw. An encampment of about twenty black recruits for the 2nd Kansas Colored Infantry occupied what is now the corner of 10th and Massachusetts. Hearing gunfire, the soldiers immediately fled to a willow grove two miles down the river, where they hid with other African Americans until the raiders left Lawrence.

“As I stood looking some three or four negroes from the camp, which was some forty rods from where I stood, came rushing by, hallooing “The Sechesh (secessionists from the Union) have come!”

Erastus D. Ladd

Raid survivor

933 New Hampshire Street

ILL-FATED RECRUITS

PARKING GARAGE AT 933 NEW HAMPSHIRE STREET

The historical marker on this spot marks the location of a small encampment of white volunteers—many of them only teenagers. A group of raiders on horseback trampled the tents and killed 17 of the 21 unarmed, unprepared recruits.

“We had no arms of any kind except an old worthless musket with bayonet, which we used for standing guard…. Before we crossed New Hampshire Street, Markham, Holloway and Cooper were down…. Charley and I ran across an open lot to Joe Rawlins back fence … when we saw some of the gang ahead of us on Rhode Island Street, I jumped the fence and turned to help Charley, when he was shot in the back and fell at my feet dead, leaving me the last of five.”

Cosma T. Colman

Raid survivor

729-731 Massachusetts Street

A DEVASTATED DOWNTOWN

729-731 MASSACHUSETTS STREET

In 1863, Lawrence’s commercial district extended only along Massachusetts from 6th to 9th Streets. Individuals and groups of raiders stopped in stores and homes throughout this area to plunder, burn, and kill. The historical marker here commemorates the House Building, which was the sole structure on its block left standing, and one of only four commercial buildings in town to survive the raid.

“By the rear doorway of the store of Duncan & Allison lay the body of D. C. Allison, who had been brought from the room where he had slept to unlock the safe, containing some $13,000 in money. After empting the safe and setting fire to the store the fiends rewarded his compliance with murder.”

R. G. Elliott

R. G. Elliott

Raid survivor

701 Massachusetts Street

TURNING POINT OF THE RAID

ELDRIDGE HOTEL

Then standing four stories tall, the Eldridge House was the largest building in town, headquarters for local Union forces, and Quantrill’s main tactical objective. Capturing the hotel would prevent any organized resistance by townspeople. The three columns of raiders converged on the Eldridge and quickly forced its occupants’ surrender. Raiders spared most hotel residents’ lives but looted their valuables and burned down the structure, in the process killing the infant child of black cook Peter Jones.

Today, the Eldridge Hotel is a city landmark, full of history and hospitality.

“We were in the company of about 50 or 60 men and women surrounded in the Eldridge House and had three alternatives, to endeavor to fight without arms, to try and escape and run the risk of being shot as we ran, or to surrender. I adopted the latter and obtained the assurance that we would be protected.”

Captain Alexander Banks

Raid survivor

727 Kentucky Street

A REFUGE FOR LAWRENCIANS

WATSON PARK

A wooded ravine separating downtown from West Lawrence served as a hiding place for many residents. The ravine is now mostly filled in and serves the community as Watson Park.

Some of Quantrill’s men rode across the single bridge spanning the ravine to look for targeted victims on the other side. Several men in West Lawrence were killed, but cornfields and hilly terrain allowed others to escape notice. An historical marker near the alley entrance on the south side of 7th Street (between Louisiana and Indiana) marks the spot where guerillas shot four prominent citizens.

“In what is now Central [Watson] park, where many found refuge by concealment in the thickets, others were flushed, to be killed by the fiendish hunters or shot like game under cover.”

R. G. Elliott

R. G. Elliott

Raid survivor

1141 Massachusetts Street

THE GUERILLAS ESCAPE

SOUTH PARK

Several witnesses maintained that the women of Lawrence were the true heroes that day. For instance, Elizabeth Fisher hid her husband, the Rev. Hugh Fisher, in a rolled carpet and dragged him from their burning home at what is now 1123 Vermont Street, near South Park.

Around 9 AM, the raiders’ scouts on Mount Oread alerted them of approaching Union troops. Quantrill and his men assembled at South Park. After four hours of looting, arson, and murder, the guerillas rode south out of Lawrence. They continued to terrorize people along their escape route and had several brushes with pursuing soldiers, but most of the raiders reached Missouri safely.

“…[W]ithin two blocks there were several charred bodies lying on or near the sidewalk, where they had been shot down and afterwards partly burned. The walls of the burning buildings had nearly all fallen, but the fires were still burning on the sides of the street, making the heat so intense that it was almost impossible to pass along the street. I stood in front of our store for a moment, almost dazed by the terrible destruction.”

Peter D. Ridenour

Peter D. Ridenour

Raid survivor

1605 Oak Hill Ave

REBUILDING AND REMEMBRANCE

OAK HILL CEMETERY

Quantrill’s men left a gutted Lawrence in their wake. About 200 male residents had been killed, some eighty women widowed, and about 250 children left fatherless. Additionally, the business district had been almost totally destroyed. It was the single largest atrocity committed on civilians during the American Civil War.

The effects of Quantrill’s Raid rippled outward from the city. Across the border, Union officers adopted Order Number 11, which authorized the removal of any residents in four Missouri counties who were deemed Confederate sympathizers. The pitiless border war of attacks and reprisals continued for over a year until Union forces solidified their hold on the region in late 1864.

In Lawrence, survivors quickly rebuilt the town and made it thrive again. Yet they never forgot the horror that visited their community in August 1863 or the neighbors and loved ones who had died. In 1865, citizens established Oak Hill Cemetery to house victims’ remains; thirty years later, they placed a monument in the cemetery to memorialize them. This monument and the graves of many raid victims and survivors remain to remind us as the tragedy and heroism of August 21, 1863.

“Dedicated to the memory of the one hundred and fifty citizens who defenseless fell victims to the inhuman ferocity of border guerillas led by the infamous Quantrill in his raid upon Lawrence, August 21st, 1863.”

Inscription on the monument in Oak Hill Cemetery

Content provided by Watkins Museum of History