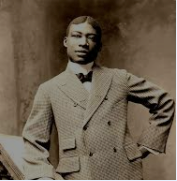

Although his story was nearly forgotten, George Nash Walker was one of the highest-paid vaudeville actors in the country who also changed the culture of Black entertainment and blazed a trail of opportunity for future Black actors and actresses.

Vaudeville was the first mass-produced entertainment in the U.S. and was popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The vaudeville shows had multiple acts such as singing, juggling, and comedy that would run in a theater repeatedly through the day. In a manner similar to cable TV, managers would acquire talent to program in their theaters. If your act could bring the patrons in, the managers would keep you. This opened up opportunities for immigrants, minorities, and people with disabilities, though they often had to suffer the prejudices of their audience.

Vaudeville was the first mass-produced entertainment in the U.S. and was popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The vaudeville shows had multiple acts such as singing, juggling, and comedy that would run in a theater repeatedly through the day. In a manner similar to cable TV, managers would acquire talent to program in their theaters. If your act could bring the patrons in, the managers would keep you. This opened up opportunities for immigrants, minorities, and people with disabilities, though they often had to suffer the prejudices of their audience.

Nash Walker developed his skills in Lawrence and left in 1893 at age 20 to find his fortune in California. There he teamed up with Bert Williams, and they started developing their act. At that time, Blacks were stereotypically characterized as intellectually inferior and dishonest. On the stage, Black characters were often played by white actors wearing blackface.

Williams and Walker turned that world upside down. They named their act “Two Real Coons” and they themselves wore blackface. They managed this topsy-turvy rejection of the prejudice of the day while using humor to project their intellectual prowess and became so popular that they were paid the modern-day equivalent of $60,000 per week.

They then turned to the entertainment industry itself. They wrote and produced the first all-Black Broadway musical, In Dahomey. Although not a commercial success on Broadway, it did enjoy a long run in England, including a performance for King Edward VII. They acquired a building in New York City that was the centerpiece of their efforts to develop talented Black performers, writers, and stage technicians. They were pioneers in popularizing Black artistry such as the Cakewalk dance and Ragtime music and were some of the first artists to record their songs.

Nash Walker didn’t change everything about the world. When he came back to Lawrence in 1902 to be celebrated in his hometown, a parade and carnival were held. As part of the carnival, there was a celebrity “jail” where Walker was “imprisoned” until people paid money to charity for his release. While in the “jail,” schoolchildren threw peanuts and bananas at Walker, and he had to accept it as normal.

Near the end of his life, Walker built a fine new brick home for his mother at 401 Indiana on the street on which he had grown up.

W.E.B. DuBois remembered Walker and his colleagues this way: “When in the calm afterday of thought and struggle to racial peace we look back to pay tribute to those who helped the most, we shall single out for highest praise those who made the world laugh; Bob Cole, Ernest Hogan, George Walker, and above all, Bert Williams. For this was not mere laughing; it was the smile that hovered above blood and tragedy; the light mask of happiness that hid breaking hearts and bitter souls. This is the top of bravery; the finest thing in service. “