Happy International Women's Day to all the women who make Lawrence great today and all those who came before. In honor of Women's History Month, we're highlighting women who spent time here in Lawrence, Kansas, and made an impact on our collective history, whether locally or nationwide.

Lucile Harris Bluford

Lucile Harris Bluford (July 1, 1911 - June 13, 2003) was a prominent journalist and a famous opponent of segregation in schools. After graduating as valedictorian of her segregated high school in 1928, Bluford became the second Black student to ever study at the University of Kansas School of Journalism. She graduated from KU with honors in 1932.

In 1939, she applied to the Master of Journalism program at the renowned Missouri School of Journalism in Columbia, Missouri, and her application was accepted. However, when she showed up to enroll she was denied entry to the program because of her race, and was asked instead to attend the all-Black Lincoln University that was 30 miles away in Jefferson City.

On October 13, 1939, with the help of Charles Huston of the NAACP, Bluford filed the first of several lawsuits against the University of Missouri. In 1941, her case made it to the Missouri Supreme Court. After two years spent in the courtroom, the state Supreme Court ruled in her favor. However, despite making 11 attempts in total to be rightfully admitted, Bluford was never able to attend the Missouri School of Journalism. MU went on to close the School of Journalism graduate program entirely in 1942, citing low attendance. Despite these challenges, Bluford worked successfully as a journalist for the Kansas City Call for 69 years, publishing weekly newspapers which addressed the unfair treatment of African Americans. The paper fought for racial justice in Missouri.

Bluford's case before the Supreme Court is often referenced as helping to lay the groundwork for the monumental 1954 case, Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka, in which the justices ruled unanimously that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional.

Despite Bluford's struggles with the University of Missouri, our neighbors to the east now recognize her legacy and achievements, honoring her as the "Matriarch" and "Conscience" of Kansas City. The University of Missouri awarded Bluford with an honorary doctorate degree in 1989. The State of Missouri recognizes July 1 as Lucile Bluford Day to honor her contributions to journalism and the state. She also received a Distinguished Service Award from the NAACP. Today, the Kansas City Public Library's east branch on Prospect Avenue is named the Lucile H. Bluford Branch. This branch of the library has powerful collections of African American Literature.

The University of Kansas Emily Taylor Center for Women & Gender Equity inducted Lucile Harris Bluford into their Pioneer Woman Awards in 2017. From their site: " The Pioneer Woman winners are exemplary Kansas women who have made historic contributions of local or statewide significance." Despite spending only a few years of her life at KU, Lawrence is proud that she studied here before going on to do more great things.

Ke-waht-no-quah Wish-Ken-O | Minnie Evans

Ke-waht-no-quah Wish-Ken-O (1888-1971), also known as Minnie Evans, was a tribal chair of the Prairie Band of Potawatomi Nation who successfully defeated termination of her tribe and filed for reparations with the Indian Claims Commission during the Indian termination policy period from the 1940s to the 1960s.

Minnie Evans was born October 14, 1888, in Mayetta, Kansas. She learned to speak English and write at the Haskell Institute here in Lawrence, now Haskell Indian Nations University. Back then, Haskell Institute was an industrial boarding school which primarily focused on teaching the students certain domestic skills approved by the federal government that would be suitable for small town and rural life. Conditions were harsh, and the institute would punish students for speaking their native tongue.

During the Great Depression, the nation found itself in turmoil, and life in Kansas was particularly hard due to the Dust Bowl. The wells on the reservations dried up, farmland was stripped by the drought eroding the fertile topsoil, and livestock had to be sold or given away. Kansas officials refused to provide welfare assistance to Native people, claiming inadequate funds, and federal programs to provide assistance to Native people were consistently delayed or blocked.

During this time when the Prairie Band of Potawatomi Nation were forced to be increasingly self-reliant, Minnie Evans rose as a prominent leader among her people. She advocated for retaining and honoring traditional Potawatomi customs, and rejected the forced citizenship of tribal peoples as well as the forced conversion to Christianity.

In 1946, the Indian Claims Commission passed an act intended to settle, for all time, any outstanding grievances or claims the tribes might have against the U.S. for treaty breaches, unauthorized taking of land, dishonorable or unfair dealings, or inadequate compensation. In response, the Potawatomi established a Tribal Council Claims Committee, and on September 16, 1947, Evans was elected by a general council of the tribe as the tribal chairwoman. The Potawatomi ultimately filed 19 cases for treaty breaches.

The U.S. Congress introduced bills in the early 1950s with the express intention to terminate the United States legal recognition of and obligation to certain American Indian tribes, including the Potawatomi. On February 18, 1954 a hearing occurred in Washington, D.C. regarding the United States government’s attempt to terminate federal supervision over these certain tribes. Three members of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation attended the hearing and spoke on the tribe’s behalf, including Minnie Evans. The following is an excerpt from her testimony.

“Senator Watkins: Why do you not want this bill?

Mrs. Evans: We are opposed to the termination of Federal supervision and control over the Prairie Band of Pottawatomie Indians on the following grounds:

A. The original treaty guaranteed these Indians rights to hold on

to their lands or allotments free from taxation or any other change.

B. The Prairie Band rejected the Reorganization Act, desiring to remain under their treaty laws.

C. Extending all rights of citizenship would subject lands to local taxation and possible confiscation owing to the financial conditions of the Indians.

D. We desire continuation of supervision and management of the Government by Federal supervision. It is a home for our parents, ourselves, and our children.

That is what I gave you there. We desire to hold that land in common and to be a home for the Prairie Band Indians. That is what I wanted to say.”

The testimonies of Minnie Evans, her two companions, James Wahbnosah and John Wahwassuck, and representatives from the neighboring Kansas Kickapoo, successfully enabled the Kansas tribes to escape termination.

In honor of this strong and tenacious woman, we encourage you to support the Native peoples and tribes of Kansas today. Consider taking a walking tour of Haskell Indian Nations University and visiting the newly revamped Haskell Cultural Center.

There is so much more to learn about Minnie Evans and the Prairie Band of Potawatomi Nation! If you are interested, please visit the official website of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation.

The full transcript of the contentious February 1954 hearing, including Evans’ complete testimony (beginning on Page 21), can be found here.

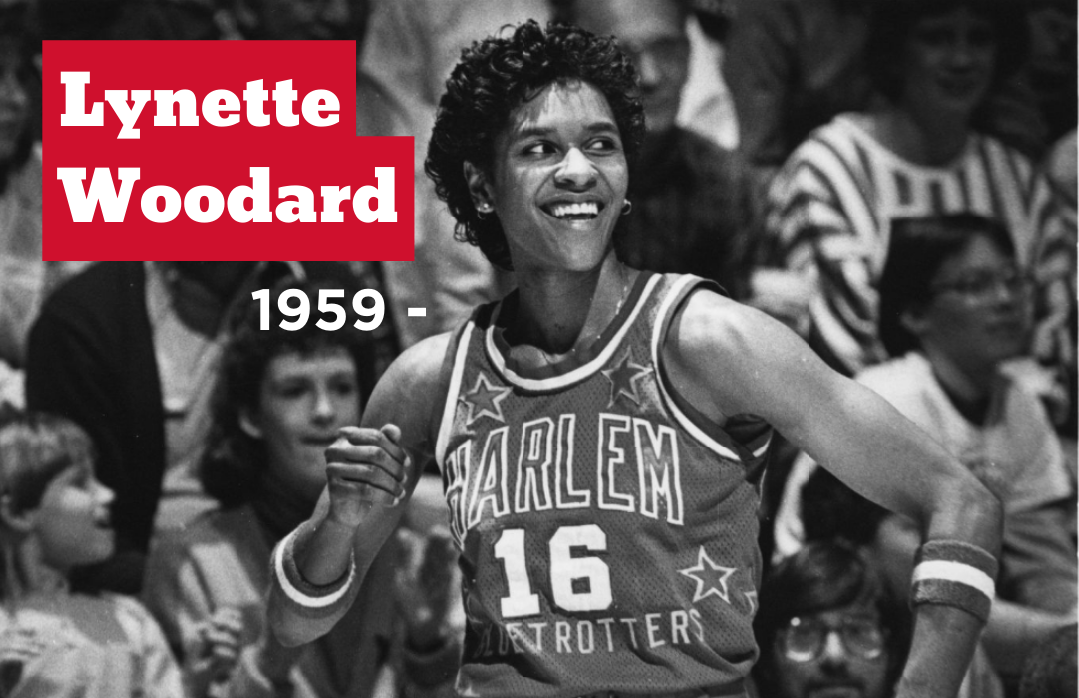

Lynette Woodard

Lynette Woodard was born August 12, 1959. Woodard is a retired Hall of Fame basketball player, a former women's basketball head coach, and the first woman to join the Harlem Globetrotters. She started her basketball career here in Kansas at Wichita North High School and played for the University of Kansas Jayhawks from 1978-1981.

At KU, Lynette Woodard was already a star. She averaged 26 points per game, scoring a total of 3,649 points in her four years in Lawrence. She was a four-time All-American while at KU, and was the first KU women's basketball player to be honored by having her jersey retired.

On January 6, 1981, the KU Women's basketball team played Stephen F. Austin University. The game was a monumental one, because Woodard, KU's star senior forward, sat tied with former University of Tennessee star Cindy Brogdon for the career scoring record of the Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women, and she hoped to beat the record that evening. Woodard soon became the record holder after a perfectly timed jump shot, after which the game was briefly halted while her teammates celebrated with her. Woodard scored 22 points total in that game.

After graduating from KU with a BA in Speech Communications, Woodard played basketball in Italy for several years before returning to the US. In 1984, she was a member of the United States' women's basketball team that won the gold medal at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, California.

In 1985, the Harlem Globetrotters invited Woodard and 25 other women to try out for the team, despite their own skepticism about the ability of female players to do well on the team. Woodard was signed to a four-year contract in September of that year, becoming the first female player in the team's history. In January of 1986, 11,000 spectators came to Allen Fieldhouse to watch her and the Harlem Globetrotters play.

Woodard was the assistant coach for the KU women's team in the 2003-2004 season and served briefly as interim head coach when Marion Washington had to step down due to health issues.

In December of 2022, it was announced that Woodard was returning to the Harlem Globetrotters in the role of Special Advisor, and hopes to increase the representation of women athletes within the organization.

In honor of Woodard's time as a Jayhawk, we'd like to encourage folks in the area to support the current KU Women's Basketball team. They are playing the BYU Cougars for the first round of the 2024 Phillips 66 Big 12 Women's Basketball Championship.

Want to learn more? Read this great article by Mark D. Hersey.

Lucy Hobbs Taylor

By Dr. Bob Dinsdale -

Lucy Hobbs Taylor learned that when you're the first, your effort has to be so much greater. You have to be greater than the prevailing societal certitude that you can't or shouldn't. You have to be greater because there aren't any maps. You must make the path and then walk it.

Lucy Hobbs Taylor knew a thing or two about the challenges facing female trailblazers of the mid-nineteenth century. She was the first woman in the world to be awarded a doctorate of dental medicine. Later in life, Hobbs Taylor was also active in political efforts for women's suffrage and hosted rallies with Susan B. Anthony in Lawrence. Continue reading >

Eleanor Coffin Henley

By Dr. Bob Dinsdale -

Eleanor came to Lawrence in 1878 with her husband, Albert. They were entrepreneurs from the get-go, drawn to this often-dusty town of 8,000 souls by the opportunity for business provided by the rapid conversion of the prairie lands of Kansas to farms and ranches. Lawrence had what it took--water power, provided by the water wheels of the dam owned by J.D. Bowersock. There was a vast prairie next door, rapidly being crisscrossed by railroads. Albert was a mechanical whiz, designing and building the machines that could twist strands of wire into that new-fangled barbed wire. With the power of the river, their loyal employees, and those well-designed machines, they made barbed wire fencing by the mile through their Consolidated Barbed Wire Company. They sold more of this amazing new product than anyone else in the country. Continue reading >